What is engineering psychology

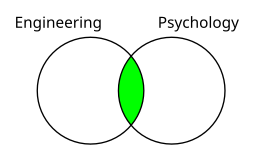

This question was posed to me on a popular question-and-answer website in 2010; since then that platform has become more closed so I’ve posted my answer here. I had no idea what the answer was when I first sat down in a course called Engineering Psychology. Paul Milgram, who eventually became my supervisor for my thesis and a great friend showed an incredibly simple Venn diagram on the overhead projector, something like this:

The goal of engineering psychology (the green overlap) is to take knowledge from psychology and apply it to Also to do research in human interactions with these systems. Here’s a video of my supervisor’s supervisor, John Senders, driving a car with his view largely obstructed, to test driving attention. Interesting work from a pioneer in the field. . Some of that overlapping zone of engineering psychology includes:

- Sensory perception

- Working and long-term memory

- Distribution of attentional resources

- Decision making behavior

Considering how humans work when designing an engineered system seems obvious but it doesn’t happen often enough. Anyway, that’s the short-ish answer, here is an example-laden explanation:

A lot of interest in the field is in systems where safety is an issue. Everyone in the engineering psychology field perks up when news stories mention human error. In the Three Mile Island disaster the state of the nuclear reactor was completely unclear to the operators—the incorrect decision is not the operator’s fault; latent failures in a system’s design are James Reason’s model of human error is often cited, his the Swiss cheese model of accident causation is well known in fields where mistakes are costly and there is an effort to improve systems (aviation, healthcare, etc). . Since those days the power industry has been transformed by engineering psychology research; and other industries (aviation is a good example) have also embraced this work.

Any doctor or nurse could easily list several glaring aspects of their work which are far from ‘user friendly,’ but only relatively recently has the healthcare industry started to wake up to human factors research. An anesthesiologist is dealing with a fighter plane cockpit’s worth of dials and knobs to keep a patient properly sedated during an operation, and then needs to pick out the correct vial for an injection (with vastly different vial contents packaged with amazingly similar appearances). To a psychologist it is not surprising that the cognitive load of the task occasionally overwhelms the operator and accidents happen. Fortunately there is current research in redesigning these tasks and systems, but we are still years away from fixing many glaring systemic problems in healthcare. Meanwhile, mistakes in healthcare are the greatest cause of accidental death in the US.

Humans are involved in every engineered system, so human psychology should be of interest to all engineers. I think a course in engineering psychology should be a mandatory part of Even if that engineer will never be involved in safety-critical system design—think of all those systems where you can tell the interface was ‘left to the engineers,’ and imagine if they were easier to use. , along with the other fundamentals. Unfortunately, engineering psychology is currently about as well-known as it was to me before taking the aforementioned elective course.

If you have any questions or suggestions, or even if you just found this post useful, send me an email and let me know! I would love to hear from you and it feels nice to know that the content I write is being read.

For more related content, look at my other posts on engineering, or under the tags ergonomics and essays. And for other topics, see thoughts and projects on the homepage. This website is my little way to give back to the world wide web. If you like this kind of post, you can sign up to a periodic email about new content (no spam and painless to unsubscribe), follow my fairly quiet twitter account, or subscribe to this website in your favorite RSS reader.

There's no comments section on this website, but if I get a notable question or comment I will include it here manually—and in that case I will ask beforehand if/how you'd like to be credited or anonymous.